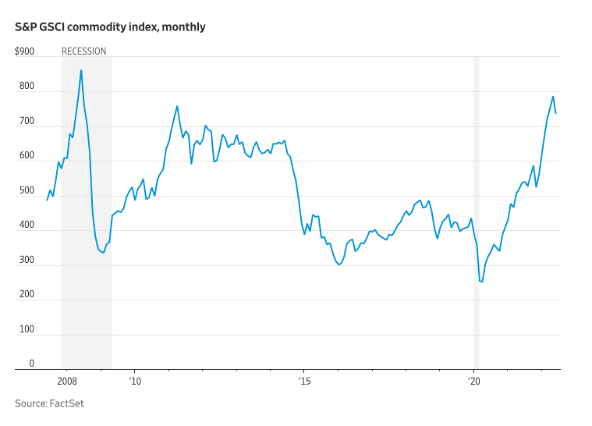

Russia’s war with the Ukraine saw the onset of a commodity price crisis during the first half of the year, with prices of oil, gas, and agricultural goods, in particular, soaring and pushing headline consumer inflation rates up to multi-decade highs.

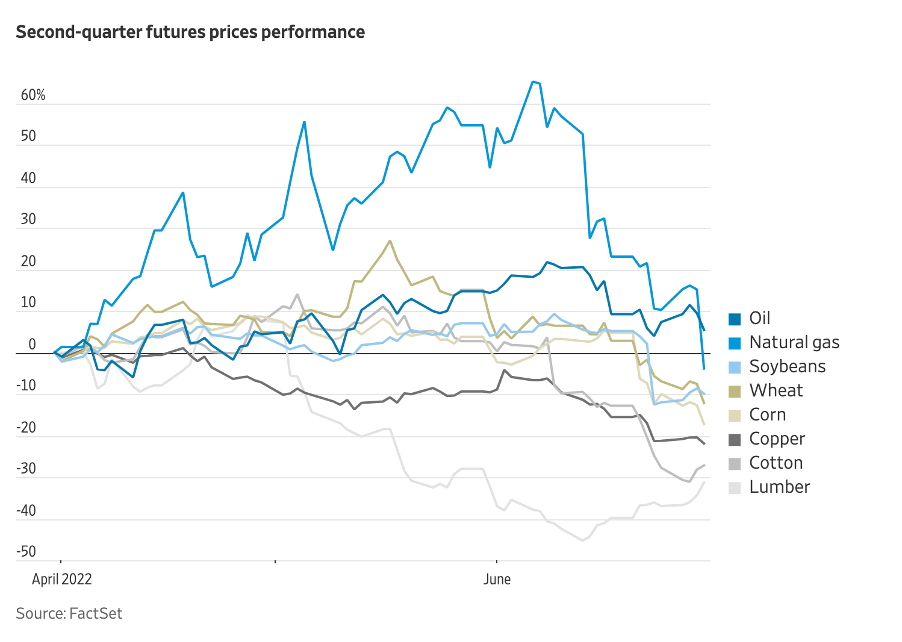

In June, however, there was a turnaround as the prospect of global recession loomed in anticipation of outsize central bank interest rate hikes, which are expected to undermine economic activity in the second half of the year.

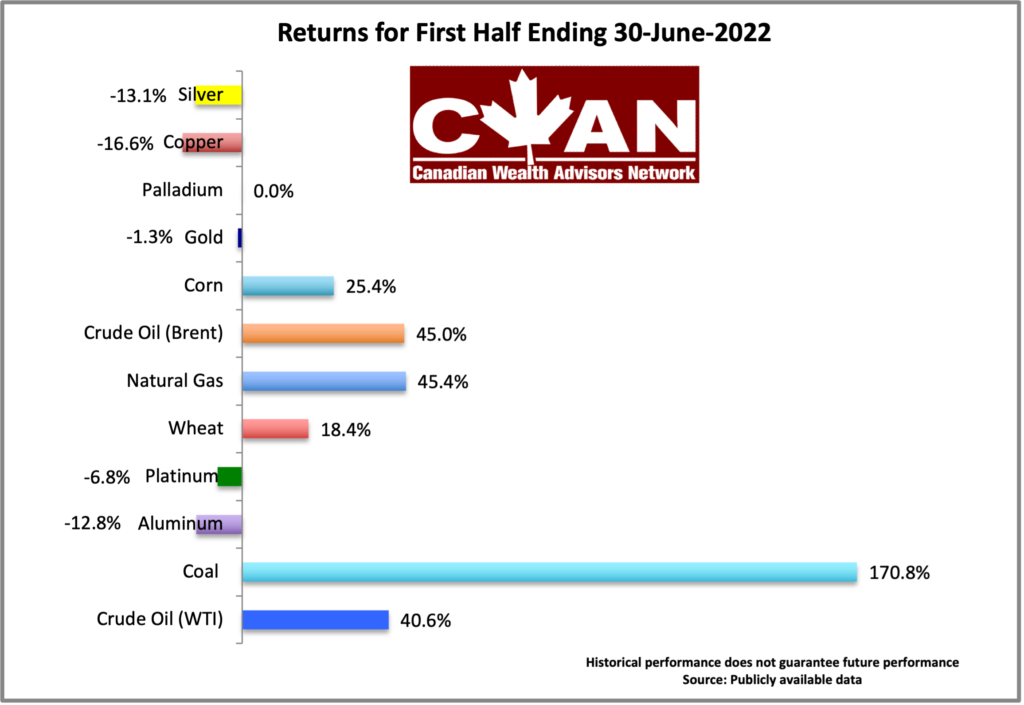

Year to date, the Bloomberg Commodity Index has increased by 18.6%. WTI crude oil prices have gained 40.6%, natural gas prices 45.4%, and coal 170.8%. At the other end of the scale, copper, aluminum, and lumber, all sensitive to prevailing economic conditions, have fallen – 16.6%, 12.8%, and 43.9%, respectively.

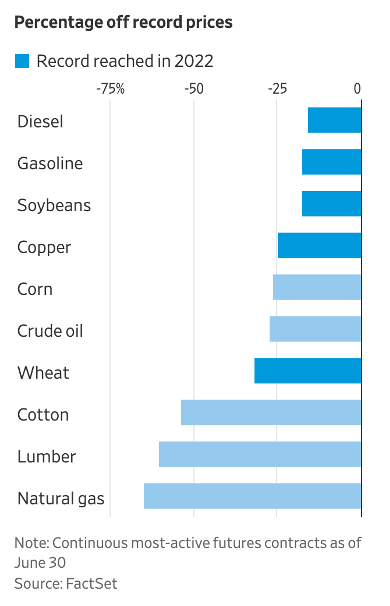

Soft commodities are still ahead at the half-year stage but off their peaks in the wake of the invasion. Wheat and corn are 18.4% and 25.4% ahead year to date but more than 25% off their peaks. Soya prices have gained 2.8% but are some 15% of their peak.

Sanctions against Russia have impacted heavily on energy and agricultural commodity prices, given the country’s huge role in providing oil, gas, wheat, and fertilizer to the rest of the world. Putin responded to financial sanctions by blockading Ukraine’s route to the market, which meant wheat exports were halted. The EU’s decision to impose sanctions on Russian oil has significantly reduced gas supplies to Europe.

The acute energy and food crises spurred by the invasion have changed the global commodity landscape, with Europe looking at ways of eliminating its dependence on Russian gas and the Western world seeking alternative sources of oil supplies.

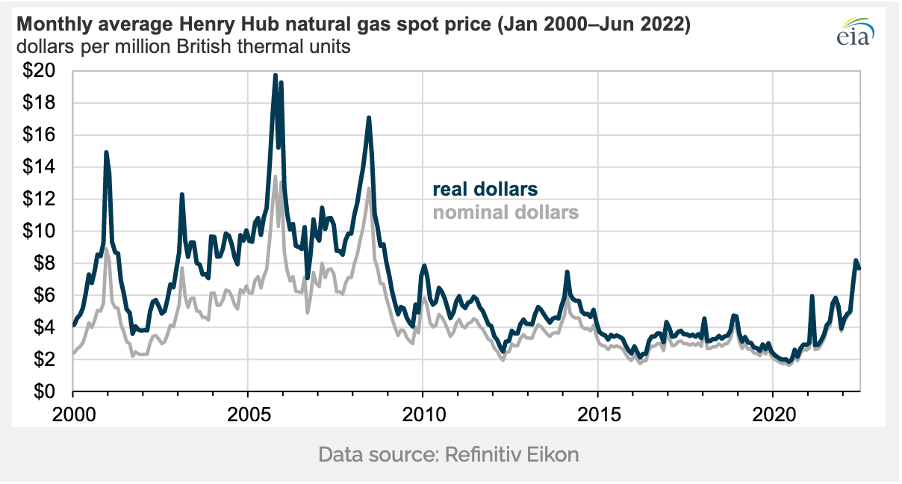

Natural gas

Europe is paying the price for the financial sanctions the Western world has put in place to put pressure on Russia to stop its war in Ukraine. Since invading its neighbour in late February, the benchmark European TTF gas price has soared more than 130%, and Henry Hub, the US gas benchmark, has doubled over the year to the end of June this year.

Countries in Europe get the bulk of their gas in Russia, with the Nord Stream 1 pipeline supplying 58% of Germany’s annual gas needs and 40% of the European Union’s. Since the war began, Russia has steadily reduced supplies to the region by 60%, prompting Germany to implement an emergency plan to deal with likely shortages as Russia weaponizes gas supply and Europe heads towards winter.

European governments have been storing as much gas as possible, in line with the EU’s requirement that they build up 80% of stores before the onset of winter. However, the reductions in Russian gas supplies over the past few months have meant that storage facilities are only about 60% full.

In the face of dwindling Russian gas supplies, Germany has put together a three-tiered emergency plan that includes alternative sourcing of gas and bringing fossil fuel power plants back on line, urging the public to reduce consumption and use gas-saving devices, and, finally, imposing gas rationing in a worst case scenario. In late June, the government moved the plan to stage 2 in response to what it envisages as a high risk of long-term gas supply shortages.

Russia’s gas exporter Gazprom announced a 10-day scheduled maintenance of the Nord Stream 1 pipeline that sceptics saw as the next step in throttling gas supplies to Europe – an eventuality that appeared even more likely with the company announcing a force majeure retrospectively and looking forward, with no end date indicated.

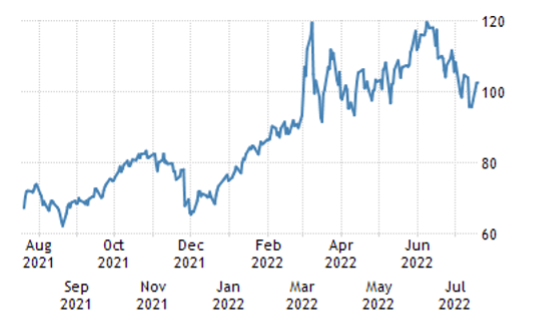

Crude Oil

Oil prices, which had been increasing since last year as economies opened up after Covid-induced shutdowns, climbed above $100 to reach a peak of $120 in the wake of Ukraine’s invasion and the sanctions imposed by Western economies on Russian oil.

However, they have since eased off to around $100 again on concerns about the outlook for the global economy and China. Private sector analysts have downgraded the government’s growth estimates of 5.5% this year to closer to 3%.

There are still concerns about the tight crude oil supplies in the absence of Russian oil. US President Joe Biden met with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman Al Saud in early July to repair relations with the kingdom and discuss the possibility of the kingdom increasing its oil production – an endeavour that proved futile.

Activity in the US oil market has picked up since last year, with the Baker Hughes Rig count, a barometer for the drilling industry and its suppliers, up to 756 rigs in the US, an increase of 272 from a year ago and up to 191 rigs in Canada, an increase of 41 on a year ago.

Soft Commodities

Wheat, corn, and soybean prices have come off their heady highs after Russia invaded Ukraine, offering some relief to food prices and raising hopes that consumer inflation may have peaked.

The easing in these soft commodity prices is unexpected given the significant role both Ukraine and Russia play in the supply of wheat to the rest of the world, with more than a quarter of the globe’s wheat coming from these countries. However, better weather, the promise of bumper crops, and concerns that the world may be heading towards a recession dampening demand have put a lid on prices for now.

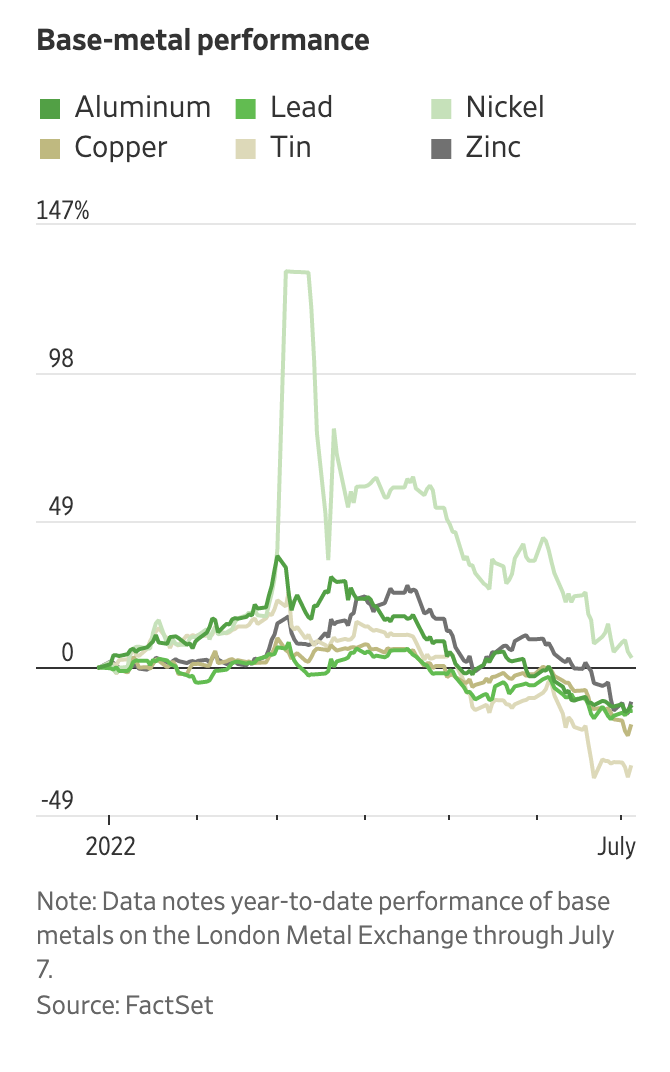

Base Metals

Base metals have fallen steadily since March on expectations of a slowing global economy due to central banks pursuing aggressive interest rate hikes to defeat inflation. A strong dollar has also played a role in the 15% to 30% declines in base metals year to date.

Copper has led the pack, declining almost 30%, and zinc prices have come off about 15% due to the energy crisis in Europe. It’s clear that, for now, concerns about demand outweigh tight supply conditions in key base metals. Stockpiles in copper, zinc, and aluminum remain low, potentially setting these markets up for a short squeeze, similar to the squeeze in the nickel market shortly after the war broke out and prices shot up 250%.

The pricing structure of zinc reflected the concerns about supply in late June, with the zinc spot price trading at a premium to futures contracts – a condition known as backwardation. Usually, buyers would pay lower prices for immediate delivery rather than a premium to future delivery prices.

Precious Metals

Precious metals are certainly not having their day in the sun, coming off sharply year to date, and not living up to their reputation as stores of value and safe havens in times of trouble.

The gold price has disappointed investors by not fulfilling its traditional role as an inflation hedge during times of high inflation. Instead, the precious metal has consistently lost ground since peaking above $2 050 earlier this year. Prices declined to 11-month lows $1 700 in mid-July after a five-week sell-off. This year, the dollar’s unabated strength has contributed to the metal’s poor performance, with the greenback’s safe haven status enabling it to achieve parity against the Euro in July.

Platinum has been even harder hit, down almost 11% year to date at $863 an ounce and 30% off its peak this year. Prospects of a downturn, signs of the automobile industry cooling down, and the war in Ukraine are all weighing on the precious metal.

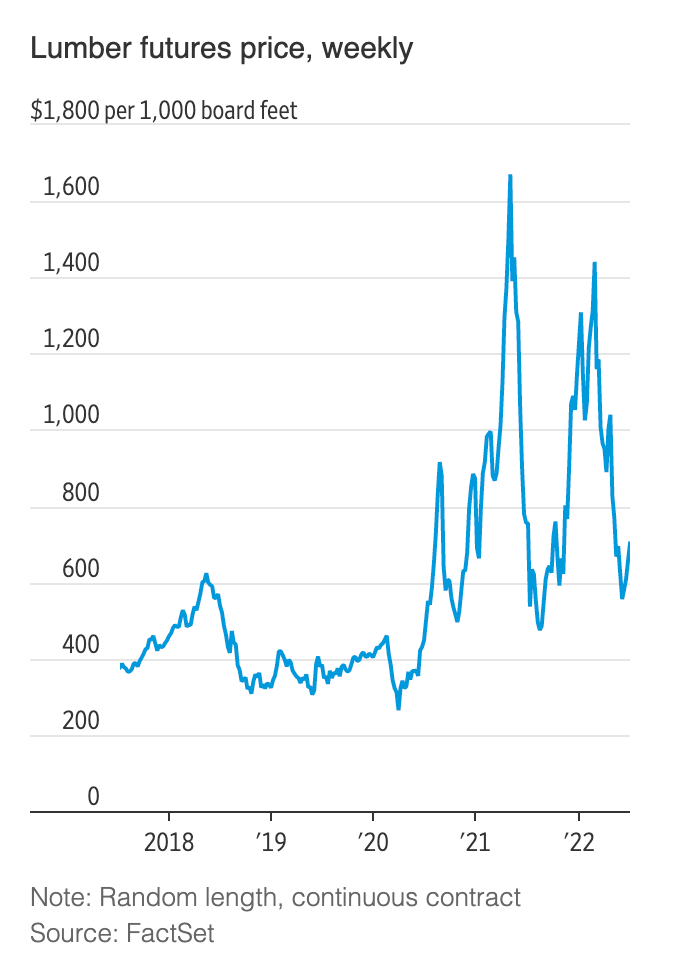

Lumber

Lumber prices have quickly come off the boil, falling almost 45% year to date on concerns about the impact of a possible recession on the housing market. Lumber prices reached record levels in 2020 as the economy came out of pandemic lockdowns. However, prices declined during the first half of this year in the face of central bank monetary policy tightening measures

In a reflection of the changing market conditions, the CME Group is changing lumber futures contracts to reflect the demand for smaller quantities from home builders, sawmills and lumber yards. The new contract will deliver a truckload of boards instead of a railcar – a quarter of the volume of wood factored into previous lumber futures contract pricing. The change is expected to take some volatility out of lumber pricing by smoothing out the peaks and the troughs.

Looking Forward

Commodity price fortunes over the next year depend largely on whether the much-feared recessionary conditions materialize as a result of central banks raising interest rates sharply to prevent high inflation from setting in. However, the easing in most commodity prices during June goes some way towards alleviating the pressure on central banks to raise rates because they may well feed through into lower consumer prices. A return to the commodity bull market would require a cessation of hostilities in Ukraine, China, the world’s largest commodity importer, regaining its former economic momentum and the global economy continuing to recover from the pandemic.

Garnet O. Powell, MBA, CFA is the President & CEO of Allvista Investment Management Inc., a firm with a dedicated team of investment professionals that manage investment portfolios on behalf of individuals, corporations, and trusts to help them reach their investment goals. He has more than 20 years of experience in the financial markets and investing. He is also the Editor-in-Chief of the Canadian Wealth Advisors Network (CWAN) magazine. He can be reached atgpowell@allvista.ca