Brexit is an abbreviated term to describe the potential exit of the United Kingdom from the economic and political partnership of 28 European countries, the European Union. The term follows last year’s debate in which Greece was deemed to be close to leaving the EU and similar unions within Europe, and which was called “Grexit.” To determine if Brexit indeed becomes a reality, a referendum on the UK’s membership in the EU will be held on June 23.

Brexit is an abbreviated term to describe the potential exit of the United Kingdom from the economic and political partnership of 28 European countries, the European Union. The term follows last year’s debate in which Greece was deemed to be close to leaving the EU and similar unions within Europe, and which was called “Grexit.” To determine if Brexit indeed becomes a reality, a referendum on the UK’s membership in the EU will be held on June 23.

The “Remain” (in the EU) and “Leave” groups of the UK voting public are approximately equal at present, if the polls are to be believed. Most polls, however, show the Leave camp with a marginal lead. The Ipsos MORI poll from June 17, for example, shows Brexit with 53% of the vote, and Remain with 47%.

From a demographic perspective, older age groups are more likely to support Leave, with those aged 55-64 and 65+ being the second and third strongest sets of supporters. The strongest single group is those without formal education, according to Populus analysis. As such, younger voters with a university education are more likely to vote Remain.

UK business sentiment, however, seems more tilted in favour of Remain. A survey of 3,394 business leaders conducted by Charterhouse Research recently showed that 35% are worried about the economic impact that would result from leaving the EU. This is more than the 25% who are reckoning that the economy will benefit from voting to leave. The largest group, however, thinks there will be no difference (39%).

One of the key maxims of the EU is the free movement of labour, which means that any citizen from the other 27 countries has an automatic right to live in the UK. Brexit supporters argue that the UK should more discriminately control who is entering the country, and perhaps even lower the number of people going there to live and/or work.

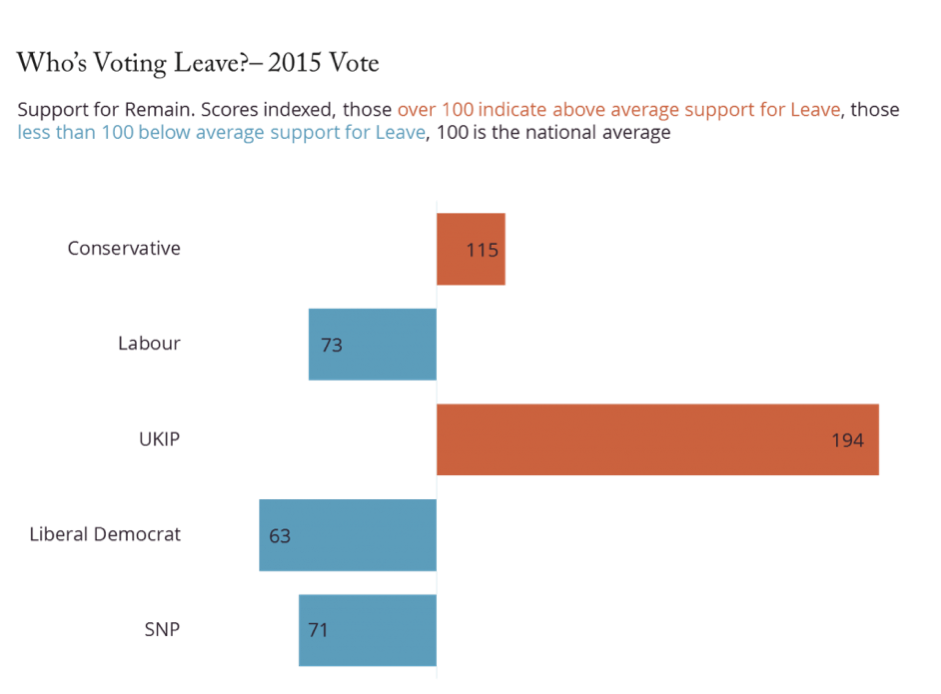

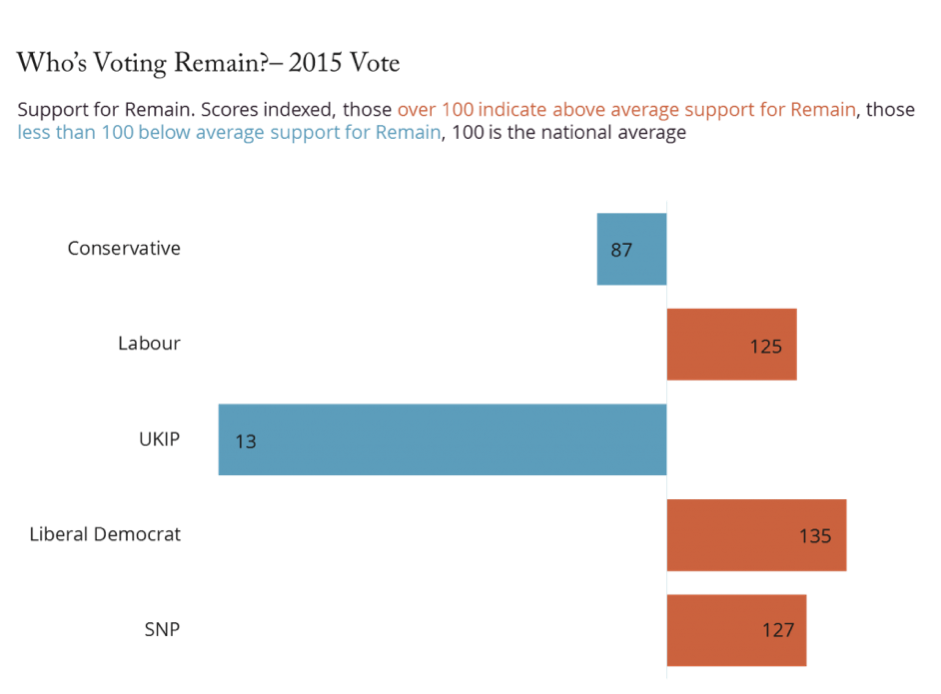

The main political parties are also fairly evenly split, according to Populus, with the exception of Nigel Farage’s UK Independence Party, which is firmly committed to – and was largely founded upon – leaving the EU:

The impact of trade balances – both of the UK and its trading partners – has been of particular concern in the run-up to the referendum. Three million British jobs are linked to UK exports – that’s more than 10% of the country’s total employment.

The “Remain” campaign, led by Prime Minister David Cameron, has argued that the UK’s economy will suffer, especially as it will lose access to the EU’s single market of over 500 million consumers. This is the free trade area in which goods can be sent without the imposition of tariffs. When it entered the UK “common market” over 40 years ago, the country’s trade volumes were significantly boosted. Should it leave, therefore, there is reason to believe that the opposite will happen.

The “Leave” camp argues that trade would not diminish upon Brexit, as the UK would make a deal with the EU to maintain trade relations, whilst also having the flexibility to negotiate its own trade agreements with the rest of the world. Because the UK normally runs a trade deficit with the remaining countries of the EU, the bloc would ostensibly be as eager as the UK – if not more so – to ensure trade is not harmed. Team Remain rebukes this argument, however, by pointing out that the UK’s total exports to the EU are equivalent to 13% of its GDP, whereas EU sales to the UK are just 3%. As such, that implies that the EU, rather than the UK, has the bargaining power.

As a compromise, some would be keen to follow the lead of non-EU members Norway and Iceland, which can access the single market by paying an annual amount into the EU budget. This provides them with European Economic Area membership, but not EU membership. Others supporting Brexit would prefer not to agree to any deal with the EU. This would render the UK in a position similar to other international nations such as the US and China, whereby the UK would simply trade with the EU under the framework of the World Trade Organisation. That would mean, however, that UK exporters would face the EU’s common external goods tariff. Car exporters, for instance, would be met with a 10% duty.

The post-Brexit trade arrangements that are (or are not) in agreement with the EU are pivotal in determining the UK’s economic fate. Brexit supporters have highlighted a recently concluded deal between the EU and Canada. Under this model, the UK would no longer have to let workers in from the union, nor would they have to pay into its budget, two unpopular EU requirements among voters.

53.6% of UK exports by value are delivered to European trading partners while 22.5% are sold to Asian importers. The US is the UK’s largest individual trading partner, having imported US$66.5 billion from the UK (which is 14.5% of the UK’s total exports) in 2015. The cable rate – the pound against the US dollar – has dropped sharply since Brexit became a real possibility.

Through President Obama, the US has been clear that it prefers the UK to remain part of the EU, stating that were the UK to leave, “at some point down the line, there might be a UK-US trade agreement” but that this agreement is “not going to happen anytime soon because our focus is negotiating with a big bloc, the European Union, to get a trade agreement done, and the UK is going to be in the back of the queue.” Presidential nominee Donald Trump has said, however, that if he becomes President in November, Brexit will not be an obstacle to a new bilateral trade deal agreement.

After the US comes EU member Germany with $46.4 billion imported (10.1% of UK exports). The UK and Germany have normally agreed on issues such as free trade, while Chancellor Angela Merkel has said that Britain staying in the EU “is the best and most desirable thing for us all.”

As for Canada, individuals looking to buy homes could feel additional pain from Brexit. Many predict that global interest rates, including Canada’s, will stay at historic lows, stemming from the uncertainty over the UK and EU’s economic futures. This could further increase home prices, adding pressure to the already hot Canadian housing market.

Canadian Finance Minister Bill Morneau also believes that Canadian businesses investing in the UK to access the EU market may also have to rethink their strategies. Thousands of jobs at Canadian firms in the UK could also be at risk, according to Morneau. Although Canada exports only 3% of its total amount to the UK ($16 billion), it is still Canada’s third-largest export market. Newfoundland, Labrador and Ontario are particularly exposed to weaker UK export demand, with around 7% and 5% of their respective exports going to the UK in 2015.